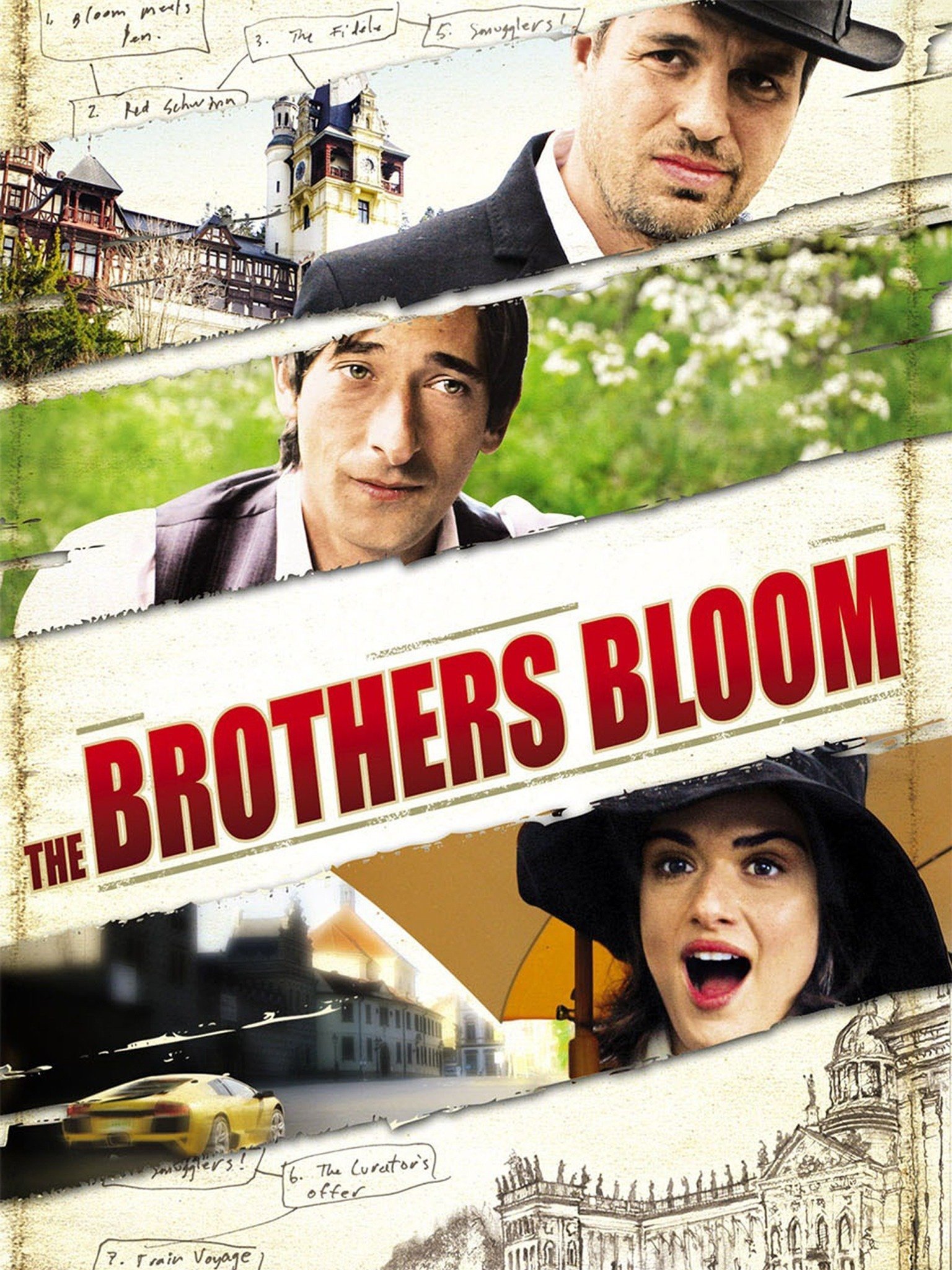

One of the things I really love about this blog is bringing hidden gems to people that they might not have heard of before or that maybe didn’t have mass appeal, but might resonate with certain audiences. And here, in the middle of my crime block, I get to do just that with 2008’s The Brothers Bloom. Rian Johnson’s follow-up to his excellent debut film Brick, a neo-noir mystery set in a high school, Johnson again plays with genre and setting in this underrated con man flick.

Starring the always likable Adrien Brody as Bloom and always angry Mark Ruffalo as Stephen, they play orphaned brothers who developed confidence schemes after bouncing around from foster home to foster home. Stephen is the mastermind, writing richly detailed stories and characters for them to act out, so that by the end of it the people they conned not only don’t know they’ve been conned, they walk away happy, feeling like they got what they wanted the whole time, never even questioning the outcome. Along for the ride is the mysterious Bang Bang, played by Rinko Kikuchi, in a nearly silent role, but one pivotal to the story as Stephen’s right hand, the quiet glue that keeps everything together (and occasionally blows it apart using high explosives).

Growing disillusioned with the lifestyle, Bloom tells Stephen that he wants out—a conversation they’ve had many times before, so much so that Stephen knows it word for word, but Stephen works very hard to keep him in the game. Resentment grows in Bloom, he wants a life where he is himself; he’s become tired of living a life written by Stephen, constantly playing his characters. Bloom wants an unwritten life, and who can’t identify with that?

Normally, Stephen is able to talk Bloom down, but this time, Bloom says he’s walking away for real and he does just that. Some time passes, but Stephen and Bang Bang track him down and, with how these things go, they convince him to head to New Jersey for one last score. They scope out the mark, to use the parlance, a reclusive heiress. Not quite a shut-in, but also not what I’d call socially adept, she lives on her own in a mansion and constantly drives her Lamborghini into things. Penelope, played by the immensely talented Rachel Weisz, shows off so much charm and quirkiness that you instantly like her; despite the attention-grabbing bright yellow supercar, she is essentially solitary. She doesn’t appear to have any friends, no job or need for a job—no one in her life at all. The perfect person to set up, really. And that they do, using the tried-and-true method of getting them to hit you with their car so they are sympathetic to you. As always, it’s Bloom who takes the hit while Stephen orchestrates the whole scheme in the background.

Now, as you can imagine, things don’t go exactly as planned—if they do, there’s no movie, so such is the way of any confidence scheme movie (or indeed, most crime films), a thing or series of things go wrong and forces our protagonists to improvise. In any case, they whisk Penelope off on a luxurious steamboat trip around the world, but only after planting the seed that it’s something she wants to do, long con style. She’s basically led the life of a monk (minus the asceticism; her money precludes her from ever suffering from need, so instead of having a quiet life of reflection, she “collects hobbies” instead of participating in life the way most people do), so the prospect of going on a globetrotting adventure is too much temptation for her to bear and she shows up at the dock with her luggage ready to go. And an adventure she has, meticulously written and constructed by Stephen. To complicate things, though, Bloom starts to develop feelings for Penelope and Penelope for Bloom in return. Falling for the mark is the conman version of getting high on your own supply, I suppose; the cardinal sin, the ultimate faux pas, the major bummer of the profession.

There’s not a lot new here; as much as I enjoyed this movie, it doesn’t reinvent the wheel. One of Rian Johnson’s strengths, however, is his iteration on genre tropes—that is, his execution of the film can be more important than the kernel idea from which the film grew. In that way, he builds a better wheel. He’s an expert at subverting expectations and while The Brothers Bloom could be knocked for being overly complicated, I think it fits Stephen’s character to write incredibly elaborate cons in order to not just successfully get away with it, but also to satisfy his own desires for adventure, control, and perhaps even a sort god complex. Growing up the way he did, I can understand why he feels the need to not just control the circumstances surrounding him, but to create them. Conman movies tend to go one of just a handful of ways and The Brothers Bloom is no different in that regard. But it is how well it’s executed that sets it apart from movies that could feel trite in the hands of a less talented director. The visuals of this movie, much like Stephen’s cons, are very thoughtfully and elaborately constructed as well. There were so many times when I found the composition of the shots stunning, and maybe it’s partly because I’m a big Rian Johnson fan (he’s never let me down as a director, which I can’t say about even my other favorite auteurs like Denis Villenueve and Christopher Nolan), but when he helms a movie, I can feel it. Even here, where he’s still young in his career and feeling out his own style, you can see how he sculpted his influences and became the filmmaker he is today.

We don’t have movies like Knives Out and The Glass Onion without Brick and The Brothers Bloom, and that would be a damn shame. The DNA of Rian Johnson’s later films is all here, just not as refined and perhaps not as confident to take big swings, but it’s all there. Brick relied on noir detective conventions for its adolescent private detective and The Brothers Bloom shows Johnson’s admiration for Wes Anderson’s style. Indeed, on first blush, you’d be excused for thinking you were watching a Wes Anderson movie—the costuming is not exactly contemporary, they go on a steamer ship instead of taking a plane, they’re in rustic and idyllic European towns for the majority of the film, and there’s plenty of quirkiness on display. In fact, I wasn’t sure that the movie wasn’t intended to be a period piece until Penelope showed up in her Lamborghini Murciélago, definitely contemporary to the time the movie was made. The inclusion of Wes Anderson mainstay Adrien Brody felt almost like an intentional homage to the distinct director, as Brody shows up in just about every Wes Anderson movie I’ve seen. But I don’t take this as a weakness of the film; I know as a writer, when I go back to my early works, I see the influences of the authors I was obsessed with at the time, namely Vonnegut and a little Hemingway, as I slowly developed my own style that owes something to my influences without feeling like a copy of them. And this is what I see in The Brothers Bloom; a young filmmaker making a movie that honors the directors he admires while doing his own thing with the way they influenced him.

As great as Mark Ruffalo and Rachel Weisz are here, it really is Adrien Brody that makes this film. His performance is a true standout in a movie where the other actors are the ones dropping the more poignant and memorable lines (particularly Rachel Weisz), but his talent to be convincingly exasperated, bemused, and relatable all at the same time is on full display. The movie—and Brody’s performance as Bloom in particular—speaks strongly to the fear that we don’t really know who we are, that we are just pretending to be who we think we’re supposed to be. That we’re all just playing a part written for us by someone else and our place in the world is prescribed by others. It makes us wonder what it would mean to step out of the role that society, our families, and other outside forces have coerced us into playing. In a world where so many of our virtual interactions are fake—bots on Twitter, propaganda and disinformation on TV, social media influencers showing us carefully curated stills from an existence as manufactured as one of Stephen’s cons, do we even know how to be real anymore? Do we even know what’s real anymore? Of course, the movie couldn’t have been written with that in mind—in 2008, Facebook and Twitter were still in their infancy and Instagram was still just an idea. But Bloom’s situation feels more relevant now than it was when the movie came out. It’s not just our personal insecurities now, it’s our entire world that’s in question.

Bloom shows us that sometimes learning to be yourself is an act of courage. And sometimes an act of courage, even in a fake world, can be very real.

Like every great comedy, like every great piece of literature, really, there is a stream of sadness that runs through it. The best comedies give us laughs through the sadness and that’s what makes them great instead of just silly fun—not that silly fun is bad, you need that too, but it’s sadness that elevates a comedy. Fleabag, Lodge 49, Safety Not Guaranteed, etc. are all comedies that really prove that and while The Brothers Bloom may not hit that upper echelon of comedic cinematic literature the way those do, it’s not too far off, and it’s Bloom’s sadness and malaise that push it so close. Because life is full of sadness, it’s full of loneliness, it’s full of disappointment, but it’s through all that where we find joy—it’s why every laugh means so much, why a genuine smile feels so good, why finding a connection with another person is so meaningful. The Brothers Bloom is a wonderful movie where nothing is real but the stories we tell and the beauty we find in the world between endings. Streaming on Peacock, Prime Video, Tubi, and Pluto TV, The Brothers Bloom is 1 hour and 54 minutes well spent. Like the uplifting Be Kind Rewind, don’t let the 68% RT score keep you away; it may not be for everyone, but this is one hidden gem that deserves a chance to con its way into your heart.