It’s that time of year again. Spooky season. And thus kicks off the Study Room’s special Halloween coverage, where I will be posting twice a week on the run up to the last fun holiday of the year, All Hallows’ Eve! I’m pretty excited for this and I’m looking forward to giving you twice the hidden gems, twice the shivers down your spine, and twice the deep dive analysis.

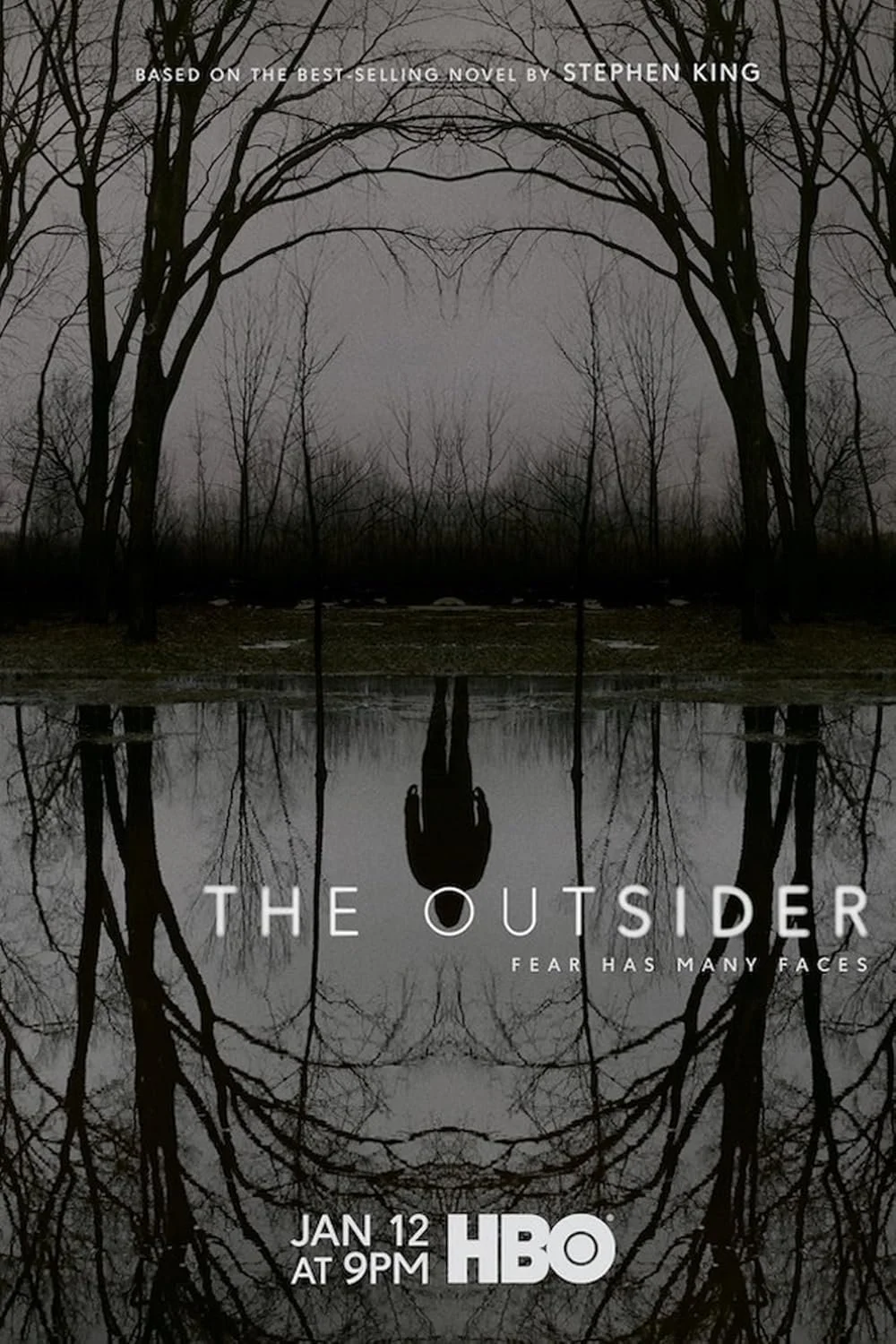

As you know, horror isn’t really my most favored genre, but I do love when horror, like science fiction, uses its themes to get deep into the human experience through the use of the fantastical, and in the case of horror films, dread. So I want to start off with one of my favorite horror shows of all time, the underrated and largely unknown The Outsider. Unfortunately, it came out in 2020, which was a big year for a lot of reasons that you may remember, and on top of that, it was overshadowed by its own network’s Lovecraft Country later in the year. So despite it being a Stephen King adaptation, it’s gone largely missed and forgotten.

[Now for a content warning—this post will contain discussion of child murder and self-harm; if that’s not something you want to read about, hit the eject button and I’ll be back next time with something less disturbing, but still spooky]

Man’s best friend discovers a parent’s worst nightmare. We start with overhead footage of an idyllic suburb that quickly gives way to the hint that something very wrong is hiding. As so many of these things begin, The Outsider opens with a man walking his dog when they happen upon the body of a small child, Frankie Peterson. Any child’s death is upsetting, but this is especially so—dismembered and eviscerated, with human teeth marks present. The scene is truly, truly horrifying in a way that sent a shudder through me. The show doesn’t hide from how disturbing this is, even the man who discovered the body is close to catatonic from what he’s seen.

A few days later, Terry Maitland, played by Jason Bateman (Arrested Development, Game Night), is getting his family ready for a little league game. It’s a stark contrast to the opening scene, but all is not well. Detective Ralph Anderson is laying on his dead son’s bed. Unlike the victim at the beginning of the episode, his son very unfortunately lost a battle with cancer; but the grief he’s experiencing is no less palpable. Ralph, played by Ben Mendelsohn (Rogue One, Andor) is still overwhelmed by the weight of the loss of this son, but he’s ready to make an arrest. One of his neighbors committed a terrible, heinous crime against the most defenseless of victims. The drive to the arrest gives the opportunity for flashbacks. Ralph telling the Peterson family about the discovery of their son Frankie, witnesses seeing Frankie get into a van with Terry Maitland, another witness seeing Terry leaving the crime scene covered in blood, including his face and around his mouth while making a feeble excuse about a nosebleed. Ralph wants the arrest to be very public—the game was a coming together moment for the community, a time when neighbors were going to go do something normal in the wake of tragedy. Not to forget the loss of Frankie Peterson, but to be there to support each other when fear and loss grips them all. Ralph wants the community to know that the man—the monster—who did this to young Frankie is being brought to justice. But when the officers show up to arrest Terry, he’s in good spirits. He seems to be coaching the team well and appears to genuinely care about the kids. Terry is in total shock and disbelief when he’s being arrested; he cannot fathom why they thing he did what they’re accusing him of doing. As he’s being escorted, in handcuffs, off the field, he takes a moment to tell the first base coach to take over; even in that moment, he’s thinking of the kids. That doesn’t seem like the action of a cold blooded, cannibalistic child murderer, does it?

And yet, despite the numerous eye witness accounts and a mountain of DNA evidence, it turns out they might not be. Because there was also a teachers’ conference in another city that he was definitely at during the time the murder was committed. But as Ralph and GBI investigator Yunis Sablo, played by Yul Vazquez (Russian Doll), trace Terry’s steps, they get so much evidence that the DA starts champing at the bit, absolutely thrilled with the insurmountable proof piling up against Terry. Eyewitness reports after the murder, CCTV footage, a taxi dispatch call (that he insisted on being made), even a handprint under a security camera he all but winked and smiled at; it’s a slam dunk for sure. Except, well, there’s video footage of Terry talking against banning books in schools in a city miles away. Can’t be in two places at once, can you? Well, when the police execute their search warrant on the Maitlands’ home, a crowd gathers, watching the home get torn apart and the distraught wife and children of the alleged killer try their best to not have a complete breakdown under the stress. As we’re there, watching the scene unfold, the camera focuses on one mysterious hooded figure—or as I started to refer to him in my notes, the Hooded Disfigure—watches on intently, soaking up the distress caused to the Maitland family. The shot and the length of time that the camera lingers on him means that, in case you forgot that we’re in a Stephen King story, there is much, much more to this man than the average onlooker. You can barely see his dark, otherworldly face under his hood, but when you do, he stares right through you. Not the camera. You. Well, me anyway. It’s a chilling visage to behold, a clear indication that something was wrong here, even more than the child murder. And you got the distinct feeling that he was doing more than just enjoying the fallout of his handiwork. No, this was a monster in more ways than one and he is not finished.

Unfortunately, the Peterson family was not able to avoid a complete breakdown. Frankie Peterson’s mother is so overcome with grief that she suffers serious medical trauma and dies. Frankie’s brother doesn’t make it either, choosing a very violent end. And Frankie’s father, with his whole family dead in a matter of days, he attempts suicide and ends up braindead as a result. The whole family destroyed. All that pain. All that grief. It consumed them. And that makes the Hooded Disfigure very happy. Ralph is a likable sort; he’s a good cop, flawed sure, but good. He’s still deeply affected by the loss of his son, but it doesn’t stop him from being there for others. Including his wife, who is grieving just the same as he is. As a side note, I really love how Ralph and his wife Jeannie’s marriage is depicted in this show; it just feels like such a caring and supportive partnership, it’s really refreshing to see, especially in a show where you’d expect to have the hero cop with his put-upon wife who revels in the sacrifice her family is making for her husband to be a cop. Anyway, Ralph is a lot like me. He’s rooted in reality; he’s not superstitious, he’s not religious, he doesn’t put stock in the evidence of things not seen. He’s that just the facts kind of guy who wants to find a logical explanation for things, but he’s stymied. What’s the logical explanation for irrefutable proof that the same person was in two places at once? What’s the logical explanation for visits to a young girl in the middle of the night by a mysterious, hooded figure who somewhat resembles her father making threats and demands? What’s the logical explanation for a trail of unexplainable gruesome child murders where each killer has an airtight alibi? You feel for Ralph; he doesn’t know he’s in a Stephen King story either and that seems to get in his way.

Enter Holly Gibney. That’s a name King fans will know, but she’s a new one to me. Here, she’s played by Cynthia Erivo (Wicked, Bad Times at the El Royale), and she is a rare one. Ralph doesn’t like unexplainable things and Holly is pretty unexplainable herself. I don’t really know the best way to describe her, but she has perfect knowledge of things she could never know. The attendance of baseball games she’s got no familiarity with, she can tell what any car is just based on the exhaust note (even Memphis Raines would be jealous), and she can look at a building and tell how tall it is, within a few feet. She has no explanation for how she’s able to know these things and neither do the doctors that have been testing and poking and prodding at her for her entire life. As evidence mounts that continues to not make any sense, it’s Holly who first comes to terms with the idea that if something can’t be logically explained, maybe the explanation is simply illogical. Ralph needs to know that the world makes sense based on the rules we’ve figured out through science, but Holly, knowing full well that science has yet to figure her out, is more readily amenable to the idea that something here is outside the bounds of human knowledge, human rules, and perhaps humanity itself. Ralph’s singleminded quest for justice—real justice, through investigation, evidence, and process is what makes rooting for him feel so good in a time when I don’t really watch things with police protagonists, but he is everything good we convince ourselves the police are. And that’s why I like him. Holly is strange, open, curious, and almost exactly contrary to Ralph, but in the situation, knowing what you know as the audience, you immediately get behind her too (not to mention that Cynthia Erivo is a great actress and is absolutely on point as Holly). Obviously they can’t both be right and knowing that this is a Stephen King adaptation, not a bookie in the world would take bets on who is.

Now if Ralph is everything we wish cops where, Jack is everything bad we can say about the police. He’s drunk, he’s belligerent, he doesn’t particularly care about justice, and he’s a man so driven by the desire to kill that he decided on a career where he would have the chance to do it on a professional basis. His wife left him, which I get, because he’s a miserable sort of bastard who loves the power trip his badge gives him. It’s no wonder he becomes an easy target for the Hooded Disfigure. Through Holly’s research, she comes up with a list of names for the Hooded Disfigure and starts to figure out a few things about him. He’s been called many things; there seems to be many stories about what he is. El Coco, El Cuco, El Cucuy, the Baba Yaga, El Glotón Para Dolor, and so on. The last name is particularly descriptive: the glutton for pain. Just like the Petersons were consumed by their grief and pain and he kept showing up, even going to the Maitlands’ home as well while they were defending Terry from the horrific accusations levied against him. The grief eater has a name and Holly knows it now. She also thinks she’s figured out his pattern. And he’s not very happy about that. In the midst of this, angry Jack becomes a pawn in El Cuco’s game and, well, there’s a price to pay. For a lot of people.

I have a baker’s dozen pages worth of notes on this limited series and while I would love to sit here and tell you every single thought I have about it, this is such a poignant and lasting examination of grief and the role grieving plays in our lives (and even the difference between healthy and unhealthy grief management) that I want you to just watch it and I don’t want to take anything away from that experience for you. I have left out so many of even the main characters who are important to the series, but to go into each and every one of them and why and how they’ve come to be so meaningful to me, well, we’d be here all night. It’s also stunningly shot, with so many intentionally composed frames that someone who knows much more about that than I do could probably wax poetic for hours on it. And it’s so incredibly well acted, the cast is so, so good. That’s not to say it’s a perfect series, though. There are moments where it feels a little slow, but I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing. At 10 episodes, it possibly could have been cut down to 8 for a snappier, pacier show, but I also can’t think of a scene to cut. There are moments where things don’t happen, where the story isn’t being pushed forward, but it’s in those moments that we get the humanity of the series.

It’s those scenes where the characters talk to each other, tell each other their stories, talk about what they’ve been through and what may come next for them that really stick with you. It’s not the action or the investigation or the dread of El Cuco, but rather those stories that are prominent in my mind even years after I first watched The Outsider. Even not getting the picture of Paddy Considine’s (Deep Cover, Hot Fuzz) Claude Bolton or Derek Cecil’s (House of Cards) Andy Katcavage or Jeremy Bobb’s (Russian Doll, Jessica Jones) Alec Pelley in this post, you will hopefully watch the series and build as much affection for them as I have. Because this show has so much to say about the lives that we’re living and it effectively uses every character for it to get its point across. We take on so much grief in our lives. Not just our personal tragedies, but the world of it. A world where children are less safe in their schools than any time I’ve been alive, a world where we sit idly by as genocides happen half a globe away. A world where women don’t feel safe to walk the streets. Where people are interrogated and violated in public restrooms over their appearance. We carry so much of this pain and grief on a daily basis that we have to tune it out just to be functional. We make ourselves so cold to the suffering of others to manage our own that we also make ourselves cold to each other. We forget that the person across from us is just as human as we are, that they’re suffering just as we are. Those who act as if empathy is something to eradicate have it so incredibly wrong that it’s astonishing. We need more empathy, lots more; more than I can muster on most days. But believe me, I’m trying.

Alec Pelley has some words of wisdom that ring louder than a bell tower on a tranquil morning. “You take small bites. You accept what you can to keep your shit together and nothing more until you’re ready for another bite, that’s it.” They work for the moment; believing in the impossible despite it going against your entire foundation, but also for dealing with grief and trauma. You can ignore all the supernatural stuff and see this as a painful, unflinching look at the enormity of grief and loss that we as humans have to go through. We endure such unimaginable and unceasing pain and are told how to get past it all the time. But that’s not what we do, is it? No, we live with it, we carry it. Eventually, we’re able to fold it up until it fits in our back pocket, getting on with our days while managing the pain of loss—and there is some kind of tragedy in that as well. The Outsider embraces living with the grief rather than trying to ignore it. And as painful as that may feel, I think it’s probably healthier. The 10 1-hour episode series is available to stream on HBO Max and if it’s not clear by now, I highly recommend you do so if you can. It is not an easy watch, but by the end, as the dust settles and the dead are mourned, the show is hopeful and not bleak. And that makes it something I keep coming back to.