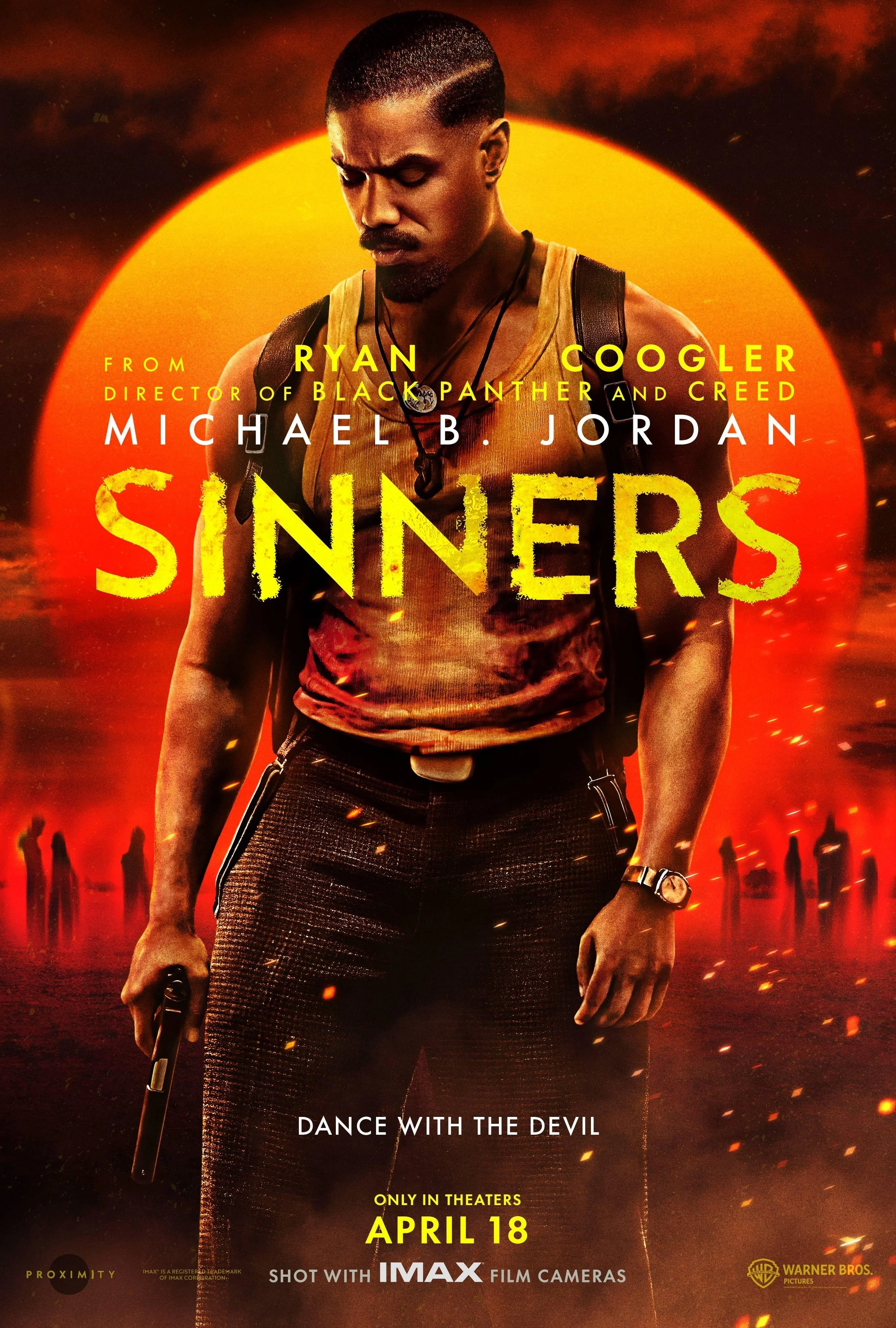

As February comes to a close, we’ve already looked at one movie that centers both love and racial equality right after we talked about a classic that intertwines romance, loss, and antifascism. Then we had a film that focused on being kind on the path to love and a break-up movie for the ages. And now, at the end of Black History Month and on the precipice of the Oscars, it’s time we get into what I believe is the best movie 2025 and completely appropriate for the month of February, writer-director Ryan Coogler’s Sinners. No burying the lede here, let’s get into it.

Sinners primarily follows the Smokestack Twins, Smoke and Stack (not their real names), played by Michael B. Jordan (Black Panther, Fruitvale Station) who come back to the Mississippi Delta after a stint in Chicago working for Al Capone. We’re talking Jim Crow-era Mississippi here, so when asked about the freedom for a Black man in Chicago and they say the racism up there is the same, it just takes a different form, it hits like a punch in the gut. Jim Crow or not, in Chicago they’re still Black and that dictates how they’re treated and what opportunities are available to them. So they gather a considerable amount of money under circumstances best not asked about and come home to establish a Black-owned juke joint, a nightclub. They buy an old saw mill to convert into their club and they have plans on putting it all together for that night. A bold plan, no doubt. I usually don’t even like making plans and going out on the same night, I need advanced warning. The twins are clearly more bold than I am and more effective too.

The first thing they notice, though, about this saw mill is that the floors have been freshly cleaned while nothing else has. It’s not nearly as subtle as some things are, but if you’re not paying attention it’s easy to miss. The twins clock the seller as Klan right away and they know that if the floor was cleaned and nothing else was, that meant it was likely because of blood on the floor. I don’t know much about saw mills, I’m no lumberologist or treeintist (and I’m far from a sawmillosopher), but I am fairly certain that trees don’t bleed. But if the Klan wanted a quiet place go about their ethnic cleansing, an abandoned saw mill with nothing around for miles seems like a good place to do it. This is such a small, interesting moment to me; it shows just how vigilant they have to be in order to survive, and every minority will recognize that scan you have to do when you walk into an unknown place to see if you’re going to be safe there or not. Either way, at the end of the deal, Smoke and Stack warn the seller that if he or his Klan friends ever set foot on their property, they’ll be shot dead, with no hesitation. The man replies that the Klan doesn’t exist anymore; just another example of how evil operates and it foreshadows the threat to come. Evil always wants you to believe it’s not a threat. It always wants to be invited in.

Helping them get ready for the grand opening is their cousin Samuel, the pastor’s son, who happens to be the best guitarist that they’ve ever known. I’m talking cosmically good here; his music is so powerful that it transcends space and time and, as his father puts it, invites evil. Sammie, played by musician and actor Miles Caton, is at odds with his father, who really feels that his gift should be used to praise god—that is, the Christian god and the Christian god only, not any religion that’s a part of their ancestry—rather than be played for people drinking, carousing, dancing, and fornicating at night clubs and juke joints. You know, those sinners.

I’m done now with the synopsis; you don’t need me to tell you that things don’t go that well on opening night and something pure and beautiful was interrupted by something corrupt and evil. Every single detail, every single moment of this film defies mere words. I spoke before of the difference between watching a movie at home and at the theaters, that sharp breath in instead of applause. And that’s what this movie is, from start to finish: a sharp breath in. There’s no moment that isn’t captivating and full of layered storytelling. To put it in perspective, I took two thirds of a page of A4 in notes in just the first 8 minutes of this film. I fear that my words won’t be enough to describe just how brilliant this movie is, but I’m willing to try. Let’s start with the acting.

Michael B. Jordan is a tour de force here as Smoke and Stack. This isn’t the case of one person playing two characters differentiated by a costume change and costume change only. Yes, Smoke wears his cool colors and Stack his fiery reds, but it goes far, far beyond that. They are easily distinguished from each other by their demeanor, the way they carry themselves, even the way they walk. Michael B. Jordan wore shoes that were slightly too small for his feet when filming Stack so he’d be ever so subtly encouraged physically to keep on the move. You know each of them when you see them; it’s an incredible performance. One thing about them, though, is that beneath that hard exterior, they act like leaders in the community. When paying a young girl to watch his truck, he teaches her to negotiate and not take his first offer. He took a moment to teach a young Black girl to advocate her worth at his own expense. In Jim Crow Mississippi. The Delta. Even the idea of the juke joint is about creating something Black-owned for the people in the community. A safe place for Black people to relax, unwind, have fun, and spend some money. Gangsters or not, you can’t help but like the Smokestack twins.

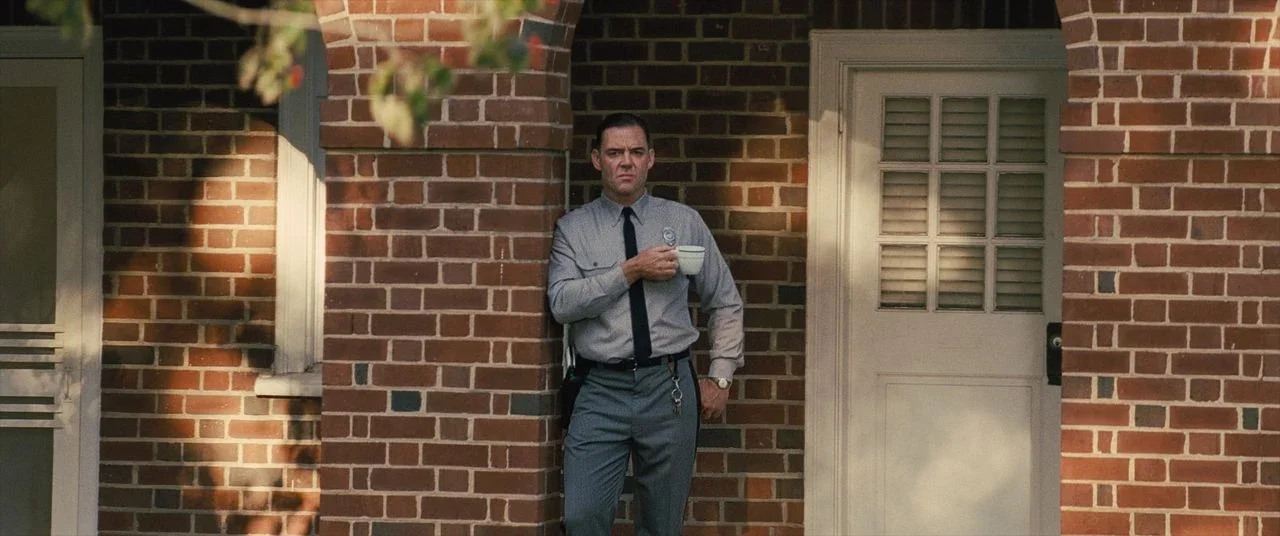

Miles Caton does a great job, he’s a young musician and actor who walked into one of the biggest films of all time to star alongside an actor putting in two all time performances and he did very well. And if you’ve been watching prestige TV on HBO or Disney lately, you’ll already know how good Wunmi Mosaku is as Annie, because you’ve seen her tear up the screen in Lovecraft Country and Loki already and she is so good here. I feel bad not taking the time to point out how good everyone is, because they all are; Hailee Steinfeld (Into the Spider-Verse, True Grit) continues being a talented actress, that’s no surprise, Delroy Lindo delivers some of the most powerful scenes in the film, especially as he recounts a story when they drive past a chain gang. His performance will move you after a career of strong performances and perhaps not nearly enough recognition. Jayme Lawson (The Running Man) has a small, but excellent role here and I can’t wait to see more of her in more films. And, oh my, Li Jun Li (Evil, Spider-Noir) is showstopping. Also, how did I not yet mention Jack O’Connell (‘71, 28 Years Later) as the Irish vampire Remmick? So creepy and yet played with so much depth.

The movie also looks so good. The way it plays with light and shadow is just so striking. There are scenes where people’s faces are in plain view, but the vampires are enshrouded in darkness, as if magically cloaked; there was no light where there should have been light. This is a movie that really benefits from 4K, not just visually, but also the music. Because not only does Ludwig Göransson (Black Panther, The Mandalorian) deliver an excellent score as he always does, the musical performances within the movie itself are top notch. When Samuel plays, you feel how his music is magical. You can feel it cut the barriers of space and time and and in one of the most inventive scenes I’ve seen on screen in a long time, you get to watch it. The action is not made of big, grand set pieces. No, it’s the exact opposite of that. It’s chaotic, visceral, bloody, and makes you not want to blink. It’s not polished fight choreography, it is not balletic. It’s raw, it’s desperate. It’s tragic and horrifying on a human level. It hurts your soul to watch. All this rage, all this hate, all this despair. Nowhere for it to go. The injustice of generations echoes through these characters, even the vampires themselves are victims of the monsters who stripped them of their humanity and forced them to become the monsters they are.

And that brings us to the crux of what I think this movie is really about. It’s not quite just a monster movie about trapped clubgoers and a pack of hungry vampires prowling outside. It’s a movie about colonialism and cultural identity. I should preface this by saying that I am still not Black, so of course I’m not in the best position to speak about the Black experience in America, but I’m going to do my best. At the heart of everything I do is learning, and the way I learn is by listening more than I talk. And if you’re reading this, you can take a pretty educated guess at how much I like to talk; so you can also imagine how much I end up listening. But what I see when I watch Sinners is the story of a people who were stripped of their identity, shipped to another continent, and had another culture imposed on them. It’s dehumanizing, to have that ripped from you and replaced with someone else’s religion being forced on you. Ultimately, I think this what drives Sammie to play his powerful music. The gospel isn’t his, but the blues is. “Blues wasn’t forced on us like that religion. Nah son, we brought this with us from home. It’s magic what we do. It’s sacred and big,” Slim (Delroy Lindo) says. And he’s right. Annie practices hoodoo, a religion developed by slaves in the south that draws on African and other practices, not Christianity. In fact, that crucifix may not be as helpful as you’d think when these particular bloodsuckers come knocking. Coogler’s choice to make Remmick (Jack O’Connell) Irish was a stroke of genius. Not only does he get to inject some incredible Irish folk music into the soundtrack (including stopping for a whole on Riverdance stage production that just works so well), he also reminds us that the Irish were colonized also. There was an Ireland before Christianity, with its own mythology and folklore. And that too was taken from them. And now, in vampire form, they’ve come to do it to Smoke, Stack, and everyone they know and care about. Remmick knows what it’s like not to be accepted in America and he’s more than happy to use that to get to the people in the juke joint.

He appeals to them by saying that the world has already left them behind. And in a way, they know he’s right. Smoke and Stack said it themselves; not even going to Chicago and working with Al Capone, who owed a large part of his success to his willingness to work with different cultures, was enough to escape racism. In Remmick’s words are a message: You have not been accepted by America, you will not be accepted, but the acceptance you crave is available with me. It’s a message that’s been parroted by those who wish to deceive for their own good; cults, gangs, abusers, politicians. It’s about appealing to the worst fears and worries and offering yourself up as the solution to those fears. They tell you that they’re the only ones on your side when all they really want is to use you for their own motives, their own goals, their own aggrandizement. And it’s all a lie. Of course it’s a lie. But in your lowest moments, in times without hope, those appeals are very hard to resist. But it’s their power he wants and that’s why he resorts to manipulation. One thing that I find so interesting here is that Remmick wants Sammie for his power; so often the trope is that the musician sells his soul to a devil in exchange for their talent, but Sammie’s power is intrinsic. It belongs to him and no one else, and it wasn’t given to, it wasn’t granted to him, it wasn’t bestowed upon him by anyone. It’s his and it always was. He was born with that magic inside him. And there’s so much power in that; this is something that he has that the vampires want from him. It’s what all colonizers seek to do—take your humanity and replace it with their commodity.

Sinners is an exceptional film. Calling it any one genre is reductive. It’s a film that uses fantastical horror to describe a real life one. It’s as genre-bending and innovative as Get Out was. And rarely is someone able to tell a story so grand, so effectively, and in such a reasonable amount of time. It’s hard to explain, but it almost feels more like a three episode miniseries than a movie, such are the different vibes of each act of the film, and each act could feel complete on its own. It could be a film about two twins coming back home to open a club and turn it into a bastion for their community. It could be a movie about vampires looking to prey on what they thought would be easy targets. It could be a film about the racial tensions that existed in America and still reverberate now. And it is. It’s all those things. And more. And it all works. But it’s also a movie that celebrates Black culture and its music and the resilience of Black people in a way that you don’t usually get to see in movies. So much pain, so much loss, so much they’ve had to endure. All of it is shown on the screen in just over two hours. This film is a masterpiece. This isn’t just the best movie I’ve seen all year, I think this is one of the best movies of all time. In the future, I think we’ll be talking about Sinners the way we talk about movies like Casablanca and Citizen Kane. I do my best not to get caught up and I try not to oversell or overhype, but sometimes it’s just not possible to temper my enthusiasm. I simply cannot get over how brilliant Sinners is. It’s a movie that will get better every time I watch it and every time I notice new things because it has so many layers to peel back before I’m certain I’ve gotten to the artichoke heart of it all. I hate to sound hyperbolic, but this feels like a generational film to me. This is simply one of the most powerful pieces of art I have ever witnessed. Sinners is, without a doubt, a perfected film. And it’s not just perfect. It’s magic. It’s sacred and big. And it is a must watch. For Black history month, for the beauty of the romance of it, for everyone at any time, Sinners is an important film that I think we’ll be talking about for decades to come. If somehow you’ve managed not to see the trailer for this, don’t watch it. Jump right in and experience the movie that has earned a record-breaking 16 Oscar nominations, including best lead actor, best supporting actor, best supporting actress, achievement in directing, original score, and best picture. Sinners is R-rated, 2 hours and 17 minutes, and streaming on HBO Max.