Sometimes there’s a name that, when attached to a project, makes you very excited to see that project. Those names often come with guarantees—Tom Cruise generally means you’re going to get a high-octane action film with great stunts, Denis Villenueve usually means you’re going to have stunning visuals and visual storytelling (even if I thought Dune was boring Christ-figure nonsense), Ryan Reynolds means you’re going to get Ryan Reynolds playing Ryan Reynolds. But for me, the number one name that gets me excited might be Mark Duplass. I know, he’s not really the A-list talent that anchors record-breaking popcorn flicks and you’re likely not going to see him headlining an MCU movie any time soon (though I would have said the same about Paul Rudd and the first two Ant-Man were delightful), but he rarely disappoints. Safety Not Guaranteed, The One I Love, Your Sister’s Sister, Language Lessons, Paddleton; when you see his name attached to a project, especially as more than just an actor, you’re in for a well crafted, emotionally affecting movie that is small in scope and will stick with you for years to come.

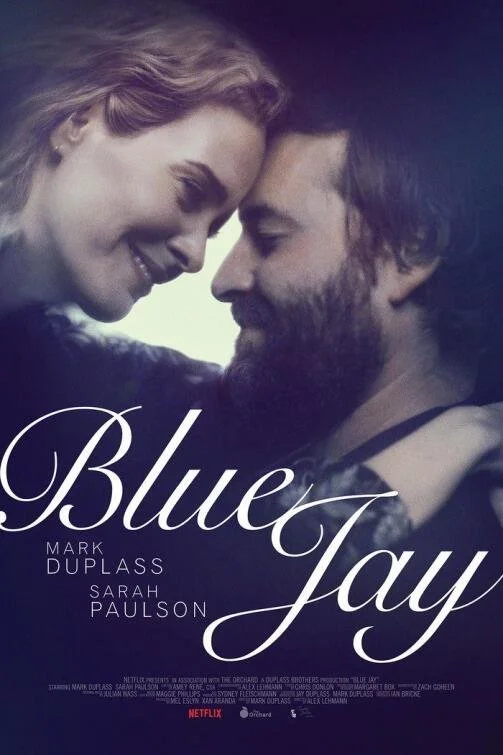

Blue Jay (streaming on Netflix) is no different. Released in 2016 and garnering a 91% RT score, it’s the kind of hidden gem that I love bringing to your attention because even I had never heard of it until I scrolled past it one day in a couch-bound reenactment of browsing the Blockbuster when you don’t know what you want to watch. Another small scale indie, it stars Mark Duplass, Sarah Paulson, and just about no one else, and is written by Duplass, directed by Alex Lehmann. Like The One I Love, this is a showcase of two actors’ ability in the craft. And like a lot of Duplass’s projects, the movie largely improvised; the script itself consisted of a two page outline that was workshopped with a woman-led creative team and then approached fairly cold by the actors. Duplass said it was the movie that he was perhaps most unprepared for in his career and that was by design. Much like the overshadowed and underappreciated masterpiece Past Lives, Blue Jay thrives on the genuine performances of its main cast and that was aided by the spontaneity of Duplass and Paulson. Sarah Paulson especially was a revelation—I’ve seen her act very well before, powerfully even, in shows like American Crime Story (she was fantastic as Marcia Clark), but I’ve never seen her act like this. It is so low key and natural and just so incredibly real. The two of them disappear into their roles in really flawless performances that make you feel like you’re there, like you’re watching a memory, not a movie. I honestly can’t speak highly enough of their performances in this film.

Memory lane is not always the most smoothly paved road to drive down. Time may be a flat circle, but we experience it as a one way street, always moving forward, relentlessly forward, whether we want it to move or not. And trying to go backwards down a one way street is at best uncomfortable, at worst inadvisable, and, most of the time, painful. Even happy memories can be tinged with sadness, because that happiness is in the past. If you’re not happy now, those pleasant memories may be fleeting moments that leave you feeling more melancholy than before. I think happiness as a state of being is somewhat of a red herring; happiness comes in moments, perhaps contentedness is more a state of being, but happiness? A smile on your face and that warm feeling in your chest? All the time? Or at least generally? I don’t think you can reasonably experience that outside of a worry-free childhood. Maybe I’m wrong and there are people who are truly happy most of the time, but that’s not been my experience. Regrets stack up, those insomniac nights, those waking somnambulisms; it takes work not to be crushed under the weight of your past decisions, right or wrong. Blue Jay is a movie about the pain of the past; the mourning of the person you used to be, the life you wanted to lead, and the loss of the fantasies of your future that wither and die as reality sets in. But that’s not to say that this is a downer or a melodrama. It’s not sappy, it’s not happy, but rather it’s the natural oscillation of life. It’s a deeply funny movie in some ways and there are moments of pure joy and happiness as the film progresses, just as there are heart-wrenching moments; it’s just like life. It’s up and it’s down, and, yet, time still marches forward. The characters play through silly little memories; they are in very different places in life and that makes things difficult. So yes, memory lane can be a painful place, but it can also be a joyful one. Life really is a mixed bag, isn’t it? The bastard.

The black and white film opens with some atmospheric establishing shots before settling in to the quiet picture of Jim (Mark Duplass) standing at the aisles of a grocery story looking quizzically at the items on the shelf when he recognizes Amanda (Sarah Paulson). Yes, I know, black and white often feels pretentious, but the aesthetic really works here to drive home the dreariness of the town in which it takes place, from where they both fled after their teen years; lacking the vibrancy of color aids the storytelling. The interaction is short and awkward and Jim is visibly upset at how it went when they part ways, only to bump into each other again in the parking lot. It’s clear from the off that they have a past and knew each other quite well once upon a time, but have long since grown apart; I’m talking patently obvious from the moment they see each other that their stories were once deeply intertwined. Jim asks her to coffee and she agrees. Amanda is in town because her sister is having a baby, Jim is in town because his mother passed away and he is there to manage her affairs. They haven’t seen each other in twenty years, but it doesn’t take long for them to loosen into an easy chemistry; after the awkwardness of the market aisles, their shoulders stop tensing and they start to catch up. Amanda is married now, she has two step sons—Jim, upon hearing this news, spontaneously cries. It’s subtle, not some over the top melodrama, and it’s not the only time it’s going to happen. He’s emotional about seeing Amanda again and clearly going through a lot in general; surely he must have figured that life goes on, but hearing it causes him to tear up. He assures her that things are fine, that his face just leaks, and tells her what’s going on with his life, which is considerably less. No family, a job putting up drywall in Tucson, and now he’s here, sitting in an empty house.

And when I say empty house, I mean a very full house, filled with memories and his mother’s belongings. It’s haunted by the past. Overstuffed with supermarket checkout line romance books that somehow make Jim confront his mortality, his room untouched, unchanged since he left town decades ago. Amanda says that she wants to see it and “the famous lovebirds”, as the only other actor, an old general store owner calls them, return to Jim’s childhood home. But not before picking up a six pack and some jelly beans and chatting more. The moments here shared between the two of them are so perfect, so incredibly powerful, such a terrific example of storytelling. It’s hard to call a movie that is basically a conversation between two people a powerhouse in visual storytelling, but it really is, because of the level of acting between these two. So much is said with body language and facial expressions; on one occasion, Jim opens his mouth to say something, but nothing comes out. Amanda opens her mouth slightly, likely to assure him that it’s okay and that nothing needs to be said, but the words don’t come for her either. And that moment is perfect. Real. Genuine. The product of an occasion that the characters are trying to navigate, not a script where everyone says the right thing all the time. This nonverbal communication between the two is just absolutely excellent, which adds to this feeling of genuineness and realness in the film. There’s something about these slice of life films—Blue Jay takes place over the course of one day; an afternoon and an evening—that can just be so powerful when they’re done right. All the clues of their past are there, they don’t need to sit down and state things that they already know for the benefit of the audience. If they sat there, eating jelly beans or drinking the bad coffee at the diner they used to go to as kids and said “Well, as we both know, we used to date in high school, it was a passionate and strong relationship that ended irrevocably and significantly and we haven’t seen each other since,” it would take you completely out of the narrative and make the movie feel like a movie, like a product. If you’ve been reading my blog for a little while, you’ve seen me appreciate when the creative team trusts the audience to pick up on cues and not need everything spelled out. When you trust your audience and let the actors shine without having to dump a lot of unnecessary exposition, I really appreciate that—when you don’t, when you feel the need to explain every little thing in painstaking and needless detail, and with repetitive retreads, it not only hurts the narrative flow of a story, it also really annoys me.

That is not the case here. This is the second time I’ve seen this movie and much like watching a mystery again, you see all the clues as to the depth of their story the second time. But it doesn’t take multiple viewings for Blue Jay to have an impact. When the penny drops, it hits you like a ton of bricks and upon a second viewing, you see how well everything was choreographed, like a ballet with talking instead of dancing (actually, there is a little dancing, to be fair). As Duplass himself said, the idea of two old flames meeting again is not new, it’s not novel, but you can tell it in a different way that is new and novel. And that’s exactly what this movie does. It’s not about star-crossed lovers who find their way back to each other, it’s not some cliched story you’ve seen a million times, even though the premise isn’t exactly original. I don’t want to tell you any more about what happens in this film because it’s something every fan of film should experience for themselves—after all, the movie is almost entirely a conversation between two people, if I tell you what they say, it would ruin the whole thing. And that would be a proper shame, because this is a fantastic movie. Sit down, put your phone away, and really watch Blue Jay, because that’s the way to really appreciate it. At a brief 80 minutes in length, it won’t take up your evening, but it might just ruin it in the best way possible. We are all trying to heal from from something. We are all dealing with something; perhaps from the past, perhaps in the present, our dystopian now. But as sad as memory lane can be, I highly recommend this film, even if you’re struggling mentally and emotionally right now, as so many are. Because Blue Jay acts as a reminder that healing is a painful, but possible process.